Armah, Ayi Kwei. 1979. Two thousand seasons. London, Ibadan: African Writers Series (Hardcover). A review on the themes by Mboya Ogutu.

Note that Two

thousand seasons (the novel), was first published by East African

Publishing House in

1973.

Introduction

“Two thousand seasons” (the novel) is a 206-page historical novel (“remembrance”).

It is a book dense in ideas that remain compelling to date. The novel is at once a deep meditation on the undoing of the black people and their necessary resurgence. It is virtually a manifesto outlining ideals lost or distorted, which remain the path to a renaissance.

The

novel is a meticulous work of art. The diction, although rendered in English, is unmistakably African in its rhythm, and is exquisitely rendered. As a simultaneously edifying, pleasurable and

a galling read, it is also a call to action. This then, is a demonstration of Ayi Kwei Armah’s consummate skill and erudition. In the review, we delve into the themes of this profound gift to the black people and

humanity in general. We chose not to dwell on other literary devices applied as

is the practice in such reviews.

The

themes

The central thrust of the novel is the need to end the atrocities, coercion, mental and spiritual degradation visited on black people. These have been amplified by the white “predators” (Arab invaders) and “destroyers.”(European invaders) It is an unambiguous call to accomplish “destruction's destruction” by returning to “The way.”

The “two thousand seasons” is a time frame symbolizing both the period of black defeat, but also the limit of the “destroyers” predominance. The first one thousand seasons depicts the descent of the black people as they lose “The way” and are overwhelmed. The next one thousand seasons, when the end of “destruction” is predicted, is complex. Here, the rise back to “The way” is sporadic, and full of confusion on purpose. Nevertheless, a critical mass of black people is predicted to eventually enlist in the return to ‘The way,” drowning out the whirlwind of “destruction’s” pervasive, divisive, and numbing disinformation. Amidst this surge, weary cynical blacks will be won over or engulfed accordingly.

The destruction of the black people is

manifold, marked by a mesh of spiralling causes and effects. What is destroyed

is “The way,” a prevalent mindset of the black people prior to their defeat. It

is averred that the root of the black people's woes has always been their

abandonment of “The way.”

The metaphor of “The way” represents

“reciprocity” or cooperation as a central aspiration and value. This social

principle of the blacks is contrasted sharply with those of the

destroyers. Their glorification of

profit and ceaseless consumption is paramount. This mentality, “keen is the

greed of the destroyer”- is bolstered by radical individualism and a disconnect

with nature’s balance. The cascade of behavioural

patterns flowing from these opposing worldviews is forcibly displayed: Creation

versus destruction. A black person

decidedly detached from the wider black world’s interests, yet believing

himself free, is a caricature. Such an “unconnected” person is unwittingly

bonded.

Parasitic relationships in society are taboo

in “The way”. Bloated hubs of governance headed by tyrants and hereditary

rulers are detested. Instead, “caretakers” are chosen by the people for their

moral uprightness and intelligence. Debate on issues is open, without the intimidation

of speakers. In contrast, King Koranche and his son rely on the armaments of

the white “destroyers” in elevating their inferior, parasitic selves over the

people. This demonstrates that their edicts are in essence, those of their

“friends.”

“The way” is related to human connectedness, undeniably

innate to nature. Studious aloofness and

detachment are the typical mindset of “destruction”. The economy, as informed by

“The way” is an enterprise that stimulates relationships. “Destruction’s” goal

is social, exemplified by distressed populations, mired in competitive envy.

This is due to manipulated shortages, leading to the concentrated accumulation

of wealth flowing to a minority.

Nevertheless, the novel is not a simplistic depiction of a pristine period of pure harmony in black society prior to the invasions of white “predators.” A faint and shameful memory of an exceedingly distant “time of men” is narrated. This era, a “festival of annihilation,” entailed vicious civil wars, stopped by the complete fatigue. The women entered peacefully, picked up the mess and established order. After enduring a period of male shirking of real work through various pretensions, they eventually eradicated male entitlement. This unedifying era, albeit blurred in “remembrance,” bluntly illustrates that black people on their own have never been immune to degeneracy.

The critical point here is that the “predators”

and “destroyers” have succeeded by employing the “ostentatious cripples” who

have always been part of the black society. More on these shortly. “The way,”

however, is asserted as the natural order and manner of reflection amongst the

black people.

Early in the novel, Anoa warns of imminent

disaster from the “wretched mendicants” emerging from the desert. And much

later, from the sea. Through their

unceasing hospitality towards these peoples, black people have courted

disaster. They have neglected to tutor these

desert dwellers on the civilizing effects of “reciprocity,” which is central to

“The way.” Anoa decries the tolerance of giving, without receiving as “the

generosity of fools.”

The identity of the black people as one, due

to their common and extremely ancient genealogy, is asserted early. We see

myriad migratory surges. From the

interior of Africa, over extremely long periods. Settlements emerged along the

way up to the “...plains before the desert…” Here, a branch of the numerous

black people sprinkled from all over Africa, settled and built a civilization stretching

over “thirty thousand seasons.” Apparent differentiations are merely a function

of geographical isolations over time. All attempted repudiation of this

underlying oneness of black people as propagated by “destroyers” is simple

sophistry, unworthy of debate.

The narrators in the novel are pervasive

through time and space. They are “rememberers,” “hearers,” “seers”, “utterers”-

protagonists at once. The narrators symbolize the single, multitudinous memory

and determination of black people. The narrators survey the farthest reaches of

history; creation, through to the abundance of black people and their descent

into horrific travails. They envision triumph after two thousand abnormal

seasons punctuating the lengthy existence of black people. They can see the African in Africa and the

African taken across the sea, to the “heart of death’s empire.” These unified

unbroken voices represent an enduring commitment against “unconnectedness.” The

assertion that black people when connected are at their best, is the essence of

the narrators’ discourse: It is

“creative work” to “...reach again the wider circle…”

Indeed, the critical pronouncement on the

“unconnected consciousness” of the black people is lucidly identified as

‘destruction’s’ most potent soul wrecking weapon. In essence, black people have

been cut off from their complementary moral and spiritual universe, into an

individualistic worldview, fraudulently

projected as freedom. Bentum, son of the degenerate king Koranche, is

illustrative of this. He presumably attains an education of sorts in Europe and

returns as “Bradford George”. This transmogrification symbolizes a variant

of the many schisms impeding the flow

of black consciousness.

As pointed out, even before the surge of the “predators” and destroyers”, there were always “rotten souls'' amongst black people. Two essential categories are identified, although their proclivities inevitably mesh. Those of inferior intelligence and flawed morals tend to disguise their weaknesses through high-handedness. These are the “ostentatious cripples” Then there are those disinclined to join in productive industry. The first group has in time transformed the role of “caretaker” to positions of license. King Koranche and his son Bentum, aka George Bradford come to mind. As alluded to earlier, the white predators provide all manner of support to these fraudulent leaders. Likewise, some slothful black people are easily hired by the invaders as “askaris” to implement violent and murderous suppression of fellow black people. In sum, “ostentatious cripples” are nurtured and equipped representatives of “destruction” in Africa.

A central pillar to the destruction of black

people's consciousness is the religions of the “predators” and the “destroyers.”

These doctrines proceeded to ignore and trash deep black thought on beginnings. It is revealed that black people did not profess certainty about who brought the earth into existence. This seeming modesty, underpinned with a truth searching attitude, is contrasted with imagined creator beings presented as fact by the invaders. We are told that black people through long observations, had discerned the existence of a pervading “creative force.” We are told however, that black people also condoned their own tales of imagined creator beings and “devils” for undeveloped minds to chew on. Subsequently, the sheer opportunism or ignorance of early black converts to these “childish” white creeds is rendered devastatingly.

The role and power of the black female resisting

“destruction” is portrayed outstandingly. This power, intelligence and resolve

is introduced in the very first chapter. Here, black women, who have

increasingly been reduced to commodities for the gratification of white

“predators” have a deadly surprise in store for them.

As priestesses and prophetesses, leaders, and combatants in guerrilla warfare against “destruction,” the black female is portrayed holding her own adeptly. Idawa’s rejection of king Koranche’s advances, notifying him of her utter contempt for him is courageous. Abena’s defiance against the same king in his scheme to get her to marry his much-reviled son is equally remarkable. This humiliation leads the king to trick Abena’s cohort of nineteen other youthful initiates for a fateful meal with his white friends on their ship. Regardless, “The way” undoubtedly demands an equality of respect between the male and the female.

Achieving “destruction's destruction” demands visions spanning beyond individual lifetimes. This is true to “The way” which is a creative process, unifying the past, present and future of the black people in the universe. A commitment to constantly exposing the pervasive and myriad frauds of the destroyers’ scheme is life’s work. Doubtfulness or cynicism gnawing at black will is sheer escapism couched in sober sounding speech. Undoubtedly, the prospect of death resulting from opposing “destruction” is a reality. However, black people must understand that death that punctures “destruction” serves a larger creative purpose. The death of any black conformist to destructions agenda provides it with an illusional aura of invincibility. Such a death is therefore a pointless event. The captive who has contracted a deadly communicable disease on the packed slave ship exemplifies a meaningful death. This is demonstrated by his decision to muster all his strength and forcefully vomit into the mouth of the slave driver assigned to toss him into the sea, thus “sharing death.”

Regardless, it is undeniable that doubt and

fear occasionally plague even those committed to “The way.” One must

dispassionately contemplate these negative feelings as they roil inside. Then,

bearing in mind that “The way” symbolizes the black collective across time and

space, the option of appeasing “destruction” to supposedly avoid individual

inconvenience is brought to focus as puny and futile.

Black people committed to “The way” must exercise patience with those who are not. They should distinguish between black people who tend to fall in with whatever scheme of social organisation (government) is prevailing, and those who decidedly support “destruction”. Within the first group, there are chances that through persuasion and example, they may join in “The way.” The latter group of blacks should be left to their devices insofar as they are a willing part of “destruction.” Confrontation with “destruction’s” proxies wherever they originate, is inevitable. The risk of sharp betrayal of those who choose “The way” is ever present. Pining memories of individual bliss could end in peril. As objects of nostalgia, even kin or friends may morph into agents of “destruction.”

However, redemption back to “The way” is open

through action. Juma, a former “askari,”

guarding captured fellow Africans for the white “destroyers,” snaps out of his

hypnotized state. In an unexpected turnaround, he aims his gun at his masters,

joining the revolt on the ship that would have transported our protagonists

across the sea to be sold into servitude. Juma, ashamed of his earlier role,

connects to the larger vision, and trains the escapees on combat tactics and

the handling of armaments seized.

END

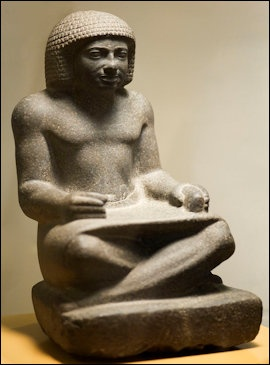

Image of Ayi Kwei Armah source: Ghana Web: Opinions of Thursday 11/8/16

https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/features/Ayi-Kwei-Armah-s-chichidodo-bird-is-a-deadly-political-animal-2-461582 (accessed on 24/5/23)

The reviewer is the the author of "The past IS PRESENT ahead of time," available at Amazon:

Comments

Post a Comment