KA2 Philosophy and Method: Ancient Kmt (Egypt) Doctrine of Opposites Modernized. 2019. UKMT Press (soft cover). USA (first printing), By Dr. Tdka Kilimanjaro. A review by Mboya Ogutu

Dr. Tdka Kilimanjaro

In this 1001 page tour de force, Dr. Kilimanjaro and his

collaborators[1] have

taken up the supreme challenge laid out by Dr. Cheik Anta Diop in the 1970s. Diop

and his colleague Professor Theophile Obenga, had in a UNESCO conference in

1974, provided compelling evidence on ancient Kemet (Egypt) as a black African

civilization. Dr. Diop’s admonished African students and scholars worldwide, to

study and research Kemet to redress the racist distortions purveyed by

mainstream Egyptology, the education curricula, and the media.

Importantly, Diop’s vision advocated for the establishment of humanities,

arts, and science studies with Kemet as backdrop. The reason he provided was that

Kemet is the quintessential classical African civilization. The deeper

objective of this profound vision was to spark the renaissance of African

culture, with Kemet as the wellspring.

KA2

Philosophy and Method: Ancient Kmt (Egypt) Doctrine of Opposites

Modernized (the book) makes a distinctive contribution towards meeting the

challenge.

We are warned that to fully grasp the concept of Ka as elaborated in the

book, one must be prepared to apply oneself. It is a richly rewarding

endeavour. This is especially pertinent to readers aspiring to use the Ka2

method of research to which we will return. Dr. Tdka Kilimanjaro, is a

supremely qualified researcher scientist. Readers will be edified by his elaboration

of the importance of properly conducted research (social or physical sciences),

as a vital tool for the liberation of Africans. Illumination also shines

through with regards to the book’s comprehensive coverage of the philosophical (and

material development) of Kemet. Here, necessary linkages to ka2 as a

research method are provided.

Structure and symbolism

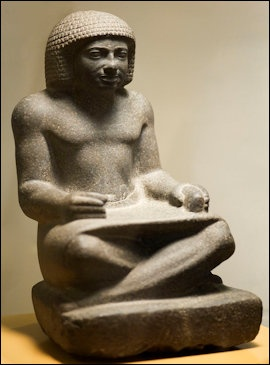

Right from the cover, the book is enriched with symbols from Kemet. Apart

from their undeniable aesthetic value they fulfill an important purpose.

Judging from the themes in the book, the symbols are selected for their power

to resonate in the African mind. These include drawings, pictures (coloured and

black & white), and terminology. Dr. Kilimanjaro reminds readers that the

pervasive Eurocentric literature that Africans must study or choose to enjoy in

their leisure, applies European symbols as a matter of course. We must imagine

the uplifting resonance Europeans and other peoples naturally experience, as

they indulge in productions saturated with symbolisms from their cultures. As we engage with these works as Africans, how

do they affect our imagination? Africans are therefore cautioned not to confuse

the pervasiveness of Eurocentric or Arab-centred literature and symbolisms to

be naturally universal.

The preliminaries include an enlightening preface where the author

outlines the arduous journey towards the creation of the book.

The book comprises two distinct, yet interrelated sections: Seshet

(section one), and Tehuti (section two).

The aptness of these symbols could not be better for the subject at hand

(the doctrine of opposites, reality as absolute movement or change driven by ka,

and the adoption of this fact as a research method).

Seshet, the “goddess” of

writing, wisdom, and knowledge, is the female companion of Tehuti. Her

husband Tehuti is the “god” who invented writing, mathematics, and

science.

Section One (Seshat) is further divided into six parts with

Kemetic-derived titles given in the evocative Medu Neter (hieroglyph) forms,

and this Roman alphabet. These are shen, ankh, djed, was, udjat and kheper.

The reader is invited to an intellectual adventure in the quest to determine

why these symbols are fitting titles to the topic at hand. This is an ingenious

stylistic device to further inculcate classical African symbolism in the keen

reader. It bears repetition here that the aim of the book is to counter the

ubiquitous Eurocentric literature that Africans have been socialised to imbibe

in.

Section One (Seshat) mainly entails a treatise on the history of ancient

Kemet. Although as noted, the two sections of the book are interconnected, this

section may be read independently. Before delving into Kemet’s history, Section

One (Seshat) begins with an exposition on matter (ssp) as an eternally

beginningless reality that the ancient Kemetyu were cognizant of in their

philosophy. In other words, the ancient Kemetyu were materialists in their

understanding of spirit as an intrinsic consequence of matter.

Further on, the tension and harmony between matter and spirit (spirit is distilled

as “will” in the book) in social relations, is expounded upon. This especially

pertains to historical unfolding of meeting of Africans with invaders, slavers

and colonizers. This sets the backdrop of the book’s critique of the overly

“spiritual” tendencies of African people (including some African-centred

scholarship and thought), in their methods of coping and fighting oppression.

The assessment is brutal: no amount of vaguely defined spirit and prayers can

defeat the objective material might and determination (will, which is spirit)

of those who continue to exploit Africans worldwide. To put this sobering

judgement in perspective, we are informed that ancient Kemet was at its best

philosophically, during the Old Kingdom, where spirit and matter were held in equipoised

tension (an aspect of Ka as discussed in the book, to which we return).

We are reminded that during this

time, the best of the civilization evolved. The famous “pyramid of Giza” built

by Nswt Biti (Pharoah) Khufu from the fourth dynasty, shows the material skills

(science) the Africans had accumulated. No building surpassed Khufu’s pyramid

in terms of its scale and accuracy in all of antiquity, right up to modern

times. The incremental domination of the

spiritual side of the Kemetian philosophy, coincided with the civilisation’s

decline and fall. Put in another way, Africans have succumbed to superstitious

thought processes for millennia and continue to pay the price for this

imbalance in thought!

Early in this section we are told that it is organized “…chronologically,

historically and logically as processes unfolding in a conceptual, symbolic

form.” This may be viewed as the outer part of the KA process of reflecting

reality. Keen readers of this section should notice it’s African centred, matter-of-fact

tone. A history book can be African-centred but is not wholly based on what the

material conditions that drove or informed the will of the people highlighted.

Although it is not explicitly mentioned, readers who are want to grasp the KA

research method will find that the presentation of Section One (Seshat) is the

fruit of the method.

Section Two (Tehuti) is further divided into four parts also

labelled with Kemetic symbols: Ka, heka, Seba and Sa. As alluded, the

author acknowledges that the concept of Ka as applied to research (processes)

is not easy to grasp. Forty-two steps are highlighted to guide the reader in

the ka research method.

In this comprehensive philosophical and practical manual, we find material

on developing moral fibre as Africans in this section too. Africans are

challenged to clarify their ideas on what morality means especially when we are

willing to do for others, what we cannot do for ourselves. More on this on the

themes section. A theory of victory is provided revealing the seriousness with

which this work was conceived and developed.

A captivating analysis of the issues between and within Africans of the

continent and Africans of the diaspora as a” struggle of opposites within the

same unity,” (the ka) is also provided in Section Two (Tehuti)

Ka2

A quick look at most definitions of what the ancient Kemetyu meant by the

term “ka” invariably comes up with “life force or double” of the person-a

feature of the soul[2]. However,

contention remains amongst Egyptologists concerning what the ka was to the

Kemetyu.[3]

Regardless, these controversies begin and end with the ka as a feature of the human

being whether alive or dead. Therefore Dr. Kilimanjaro’s extension of the concept

of ka to encompass the whole material universe including animate and inanimate forms,

phenomena (including social), and the workings of the mind, initially appears to

be a vast creative reach.

Lekov,[4]

who finds that Atum the creator, passes on “his Ka” through the lineages of

creation appears to lend support for this extended ka concept. Citing pyramid

texts, Lekov shows the king’s (nswt biti or “pharoah”) ka re-joining the

creator on earthly death, symbolizing the destiny of all human individual kas. But

then, Lekov’s study is confined to the ka as a human attribute. What about

other living things and inanimate objects and phenomena in the universe? It can

be inferred from the myth that Atum’s ka extends beyond humans as it states

that everything emanates from him. This seems to justify Dr. Kilimanjaro’s conceptualisation

of ka for this project.

Furthermore, Dr. Kilimanjaro presents the full implication of the

wholistic, dynamic and essentially dualistic ancient Kemetic cosmology and

theology. He cites the Khemenu (Hermopolitan) ogdoad, mentioned in one of

Kemet’s important cosmogonies. Ptah, emerges from waters of Nun as the Primeval

Hill and visualizes creation. Atum follows and sits on the Primeval Hill to

commence the creation process. Meanwhile, four (opposite) pairs of creative

principles have remained in the waters of Nun. These pairs are arguably the

fundamental ingredients for the universe’s creation, it is asserted. The doctrine of opposites is pervasive in this

creation myth. Dr. Kilimanjaro asserts that Ka as the doctrine of opposites is

at the core of Kemet’s foundation. Africans would do well to study this sublime

and powerful cosmological worldview, driven by ka. Then compare it to the

prevailing reductionist, positivist coldness and barreness. It is apparent from

the book’s development of the concept (Ka2) that the movements of

creation are driven by ka as the life force.

Ka is therefore a contemporary distillation of a profound and key aspect

of Kemetian philosophy that is effectively pliable as a research method to

derive correct history. This is crucial for the liberation of Africans in

today’s world. Presumably therefore, this revival and energized ancient African

Kemet concept steeped in deep philosophy, inspired the author to stamp the

exponent (to the square of) on it: Ka2.

Ka as a research methodology is

given as an intellectual tool for mirroring reality. It dispenses with ideas of

the thing or phenomenon under study. By this is meant absolute fidelity to the reflection

of its movement is mandatory. Unlike Plato’s idea as more real than the thing,

in ka, there is no absolute idea. Ka method of research is premised on movement

(change) as the absolute reality of everything. From the workings of the mind

(which is based on, and mirrors the changes in its surroundings), to infinitesimal

sub-atomic particles, right through to galaxies and the universe, all is

process. A becoming, being, transformation, or death and becoming again,

khepera.[5]

But never arriving back in the same manner or form, as movement is spiral (not

cyclical).

It is further explained that all apparent realities are necessarily unified

opposites within their existence as entities. It is their respective internal

opposites, unified in tension (eg, positive-negative; old-young; up-down;

light-dark; male-female; matter-spirit), that are the fundamental driving force

(Ka) of changes. Each opposite drives to dominate the other, even though they

cannot exist without their counterpart. It is this tension that causes movement

in nature. In the social context therefore, for instance, a race or class with

the will (spirit) and material resource can eventually subsume that of its

counterpart whose will is weaker. External influences play a secondary role. Ka

is therefore a process-oriented research method. It is designed to capture

mainly the internal oppositional movements (along with the external factors

influencing them) in symbolic form (language, numerals, diagrams etc).

Chronology and historical context shorn off any irrelevant narrative or opinion

is key in the method. It is asserted that if done properly, a plausible

movement(s) of the phenomena under study can be presented.

Important critiques

Two comprehensively addressed critiques in the book have also been

identified. As background justifications for the ka research method, they further

serve as avenues for understanding:

a)

Dr. Kilimanjaro’s searing critique of the prevalent

African-centered approach in the study of history in the last 70 odd years is

important. We are informed that some of those that have been identified as

radical African-centered works have in fact been delimited by what the

Eurocentric power structures in academia have allowed (in the context of USA

only?). Granted, many of these works have been useful in puncturing the

distortions and exceptionalisms of Eurocentric and Arab-centered narratives.

However, by giving little heed to the actual material circumstances, and

historical flow and context of the area under their studies, they are rendered mostly

unscientific. Put in another way, these works have not followed the Ka

method but are eclectic fittings to hypotheses already formed by their authors.

Africans quoting Hegel’s dialectics (thesis,

anti-thesis, synthesis, new thesis and so forth) without knowledge of ka which

precedes it by millennia and from where Hegel derives it from the Greek lineage

(who derived it from Kemetic ka) are unwittingly deferring to an intellectual

edifice that does not deserve the awe.

The

themes

It

should be clear by now that there is bound to be an overlap of this section

with what has thus far been covered. The

promotion and elucidation of a scientific basis for a Pan African outlook with Kemet as its foundation, is identified as the overall theme in

the book. Africans have a history that is fundamentally unbroken and coherent

from this classical basis (Kemet). This, regardless of the sustained

interruptions like invasions, slavery, colonialism, and neo-colonialism. Understanding

the implications of this should guide researchers in African history from ad

hoc insertions in time. Ka method of research is apt for this endeavour.

The book offers a skilful and comprehensive history of philosophy from

the African perspective. The focus of course is the doctrine of opposites, the

ka, the key to mirroring the mechanics of reality which is process. The “Greek

miracle” compiled from “fragments” handing priority of deep thought to the

European academe is surgically analysed and exposed mercilessly. Importantly, readers

are made to understand that the “theory of opposites” and “dialectics,”

supposedly rooted in classical Greek philosophy (and extended by European

thinkers like Kant, Hegel and Marx), are in fact variants of African Kemetic

thought. The very ancient African insight that all reality is composed of

dualities in tension precedes by millennia, even the Chinese yin and yan

concept. Today, the book asserts, the unity and struggle of opposites that is

all-pervasive is known as ka.

Unsurprisingly therefore, the Ka2 method of research is

unapologetically and uniquely African and is presented as a necessary avenue

for recovery from centuries of Eurocentric and Arab-centred bias and fraud in

the realm of ideas, and the study of humanities, and physical sciences.

However, it should be clear that Ka2 is a rigorous scientific method

and is therefore universally applicable.

The preceding theme segues to that concerning the application of concepts

and symbols. It is asserted that Africans must develop their own concepts

whenever applicable in their research and presentations as these have powerful

resonance whether negative (keeping Africans subservient to European and Arab

intellectual sleights) or positive (liberating the African imagination).

The prevalent African-centred forms of published material are

characterised as having played their role in the context and period in which

they emerged. As already gleaned, they mostly focussed on identifying the

distortions and omissions of Eurocentric material. These African-centred works

also set out to thrust Africans into the Eurocentric material almost haphazardly.

The overall effect was exposure of the Eurocentric project in academia and

criticism. It is conceded in the book, that these efforts served a purpose. But

an assertion is also made that they are woefully inadequate in providing

Africans a genuine reflection of what happened and what needs to happen, to

come out of their oppressed status. Dr. Kilimanjaro is clear, social theory

must be designed to “liberate.” Criticism is not enough.

Science is a vital theme in the book. Ka is a scientific method of

research as demonstrated. The critique of the dominant African-centred

publications on history already covered alluded to the overbearing inclination

towards praising the spiritual in the African. This has been at the expense of

material science. This defies the dualism, the reality driven by ka when spirit

and matter necessarily exist in balance tension.

We are told that “spirit” can only manifest through matter! Here Dr.

Kilimanjaro is incisively brutal. Merely listing African inventors is not

enough. Africans must learn how things are built, from land sea and air vehicles,

to hospitals, defence systems, how to develop reliable farming and distribution

systems, and the like. He opines that some of the discourse appears as if

Africans will somehow overcome their oppression by magically (“spiritually?”) transcending

physics. Without a cogent understanding of what exactly “spirit” is, the

bragging and feel-good talk of a spiritually-in-tune African nature has

unfolded while the enemy, supposedly without spirit, has with material science,

continued to dominate, and oppress Africans for centuries. That the Kemetyu

were firstly materialists (based on the cosmogonies with chaotic matter,

unbeing, Nun), with spirit emerging as a variant or consequence or equivalent

to matter, should serve as a jolt. And when they were in this classic mode (Old

Kingdom), we see the best in their material development, and decline from then

on as gleaned earlier, when spirit became increasingly a dominant factor in

their philosophy. Spirit is distilled as will in the book.

Arguably, related to the issue of spirit is morality. Readers are informed

that the notion that morality is necessarily a consequence of religiosity

through adherence to Judaism, Christianity, or Islam (doctrines introduced by

invaders) is a false unity. Africans had and can revive their moral systems

with maat (balance, truth, reciprocity) as the guiding principle. The

book provides an exposition of the cosmological, social, and personal reach of maat,

a sublime, all-pervasive Kemetian moral philosophy, and distils its principles.

We are told that Africans have fought for others fearlessly and with passion,

but have been unable overall, to muster this same level of spirit (will) to

fight to free themselves. This presents in sharp relief, a moral deficiency

amongst Africans. It stands to reason that a spectrum of immoral deficiencies must

already be at play if we Africans are ready to perform the ultimate military

actions for others, but rarely for ourselves.

Pursuant to the above disturbing revelations, the book contains material

with maat being the mainstay on moral teachings including admonitions

and wisdom teachings from Kemet that are applicable to this day.

A paradigm shift from the overbearing

metaphysical and liberal approaches (criticizing Eurocentric and Arab-centered

fraudulent historiographies, then insinuating Africans into them haphazardly),

common to African centered works is called for in this book. This is symbolized

by the University of Kemet as the way forward with science (material, learning

how to build things, not just talking and preaching) and will (spirit, fight

for African rights, not the enemy’s dominance).

Dr. Kilimanjaro teaches that in the case of the African situation, a social

theory that liberates is the only worthwhile endeavor.

Some issues

The book has an extensive bibliography for those who would like to

research further. It would have been useful to have an index.

Conclusion

The book is a remarkable achievement. This brief review merely scratches

the surface. The admonition to Africans to take science very seriously and

develop African concepts in their study of reality, resonates. Ka is expertly

presented as a pliable scientific method for social research including history.

The exhortation to Africans to learn how to study logically, and make and build

things cannot be ignored. We have no choice but to match matter with matter,

through our “will (spirit) to justice”. This is true in the face of the clearly presented

reasons for our (continuing) loss, as we focus on “empty spirits” talk and

debates. The book exposes Africans’ perennial

dabbling in warped morality, driven by base opportunism. These actions are in

effect diametrical to African interests.

The sublime cosmological, scientific, and spiritual mindset of the ancient Kemetyu is highlighted in sharp relief. We are advised to draw upon it as our inheritance. This is a book that cannot be read once and left lying as a “done that.” It demands serious study. It should be read in teams/study groups as Dr. Diop recommended serious African scholars to do. In a nutshell, this is a highly recommended book that brings us to the necessary paradigm it identifies in African-centered intellectual, moral and martial development. This marks an internal movement in our collective ka as we move to oppose the external forces against us.

END

[1] The book is copyrighted to Ife

Kilimanjaro, Yahra Aaneb, U-Shaka, Akua and Tdka Kilimanjaro

[2] The Egyptian Soul: The ka, the ba and the Akh.nd. University of South Florida. http://myweb.usf.edu/~liottan/theegyptiansoul.html accessed on 18/5/23

[3]Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "ka". Encyclopedia Britannica, 26 Jul. 2010, https://www.britannica.com/topic/ka-Egyptian-religion.Accessed 18 May 2023.

[4] Ancient Egyptian notion of Ka

according to the pyramid texts. Lekov, T. 2005. Pg.33, Journal of Egyptological

Studies.

https://www.academia.edu/download/35345446/JES.02_Lekov_-_Ka_in_PT.pdf. (Accessed on 18/5/23)

[5] The

Kemetic root word with the

beetle as chosen symbol (in Medu Neter/”hieroglyphics”), for coming into

existence, growth, transformation.

Dr. Kilimanjaro's image source https://www.fisk.edu/academics/school-of-graduate-studies/graduate-program-in-social-justice/social-justice-department-chair/ (accessed on 24/5/23).

Comments

Post a Comment