The

Principle Importance of Classical Kemet (Ancient Egypt) For the Kenyan

School Curriculum (Drafted in 2021)

By Mboya Ogutu*

Introduction

Fela Anikulapo Kuti’s, “Teacher Don't Teach Me

Nonsense[1]

,” identifies parents, formal education tutors and the Government

in the workplace, as key instructors through one’s lifespan. In this song, the Afrobeat

icon poses a radical question: “Who be government teacher?” The answer:

“Culture and tradition.” The song is a searing indictment on the validity of

tutelage endured, arguably, across post-colonial Africa. Africa is

fundamentally under the sway of somebody else's heritage.

Although we focus on Kenya, the thrust of our

argument applies across the African continent. Kenya’s education policies

continue to borrow from foreign curricula. This may be necessary. We argue

however, that the considered insertion of Africa’s foremost Classical

Civilisation, ancient Egypt (Kemet[2]

) into the curriculum, as a basis of who we are as Africans is

critical. Authentic “culture and tradition” is an unapologetic fusion with the

finest in antiquity. Simply put, as a principle, the inculcating of considered

features of Classical Kemet is imperative. This assertion follows from the fact

that Kemet was the first and longest lasting civilization in antiquity.

Furthermore, Kemet, through to its lofty fruition, was rooted in Africa.

The apparent nit picking serves a purpose. It

fell on Africans in the past decades, to affirm what should be obvious facts in

an otherwise fraudulent controversy. This situation sprung from the brazen

capacity for distortion by Africa’s perennial detractors. And so, in what may

seem like piddling, we now move to firmly establish who the ancient Egyptians

(Kemetyu[3]

) were. The importance of Classical Kemet to our national and Pan

African consciousness, is therefore accomplished.

The historic symposium on “The peopling of

Ancient Egypt ''[4]

held in Egypt in 1974, under the auspices of the United Nations Educational,

Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO), is an appropriate launchpad. The

masterful presentations on the melanin content found on the skin of Kemetyu

mummies by Senegalese Egyptologist, anthropologist and physicist, Professor

Cheik Anta Diop, was a crucial moment. Along with the expert linguistic support

of Congolese Egyptologist, Professor Theophile Obenga, the duo asserted the

unambiguously “negroid” and African provenance of the ancient Kemetyu. No

research has since been able to debunk the “negroid” (African) provenance of

the Kemetyu population, from inception, development, through to attainment of

their high civilisation. It is in the period categorised by Egyptologists as

“the late period” where Kemet becomes increasingly white through invasions,

genocide, intermarriage and mass withdrawal. Professor Diop’s quote on the

importance of Classical Kemet to Africa remains pertinent:

“...The history of Black Africa will remain suspended...until African

historians dare to connect it with the history of Egypt...the African historian

who evades the problem of Egypt is neither modest nor objective, nor unruffled;

he is ignorant, cowardly, and neurotic…”[5] This

brutal admonition was issued in 1973. Decades later, Professor Bethwell Alan

Ogot, who was present during the symposium had this to say in his autobiography

published in 2003[6]

: “I left Cairo with the belief, which has been fortified through mature

reflection, that just as European classical studies begin with ancient Greece

and Rome, African classical studies must begin with Egypt and Nubia”. This

is instructive. Here is an internationally renowned historian, instrumental in

setting up history faculties in the region in the early post-colonial period.

Three decades after said symposium, and an illustrious academic career,

Professor Ogot is essentially ruing a missed opportunity. Today, our education

policy makers have no excuses. The prevailing virtual black out of Classical

Kemet in Kenya’s and indeed Sub-Saharan Africa’s school curriculum is

inexplicable. It is a staggering, nonchalant disregard of our magnificent

heritage.

African youth need an intellectually honest,

spiritually uplifting, and productive vision. They do not want to be corralled

in a mould of perennial African ineptitude, destined only to play catch up. The

truth is the sensible course in this regard.

Classical Civilisation

The term “classical” suggests

long-established, universal practices and processes considered to be of

enduring utility[7]

. It is heavily associated with Greco-Roman art, literature, and

architecture. Classical Studies degrees offered by universities project these

themes. This brash “universalism” of what is in fact a particularity, is a

powerful psychological method of European dominance, according to African

American anthropologist, Marimba Ani[8] .

She explains that the various tribes of Europe eventually coalesced in the

medieval period, under a Greco-Roman cultural facade. It was only after their

Judeo-Christian expression had been internalised, did justification for

“expansion” sanctioned,” by God” emerge. Ironically, the ancient Greco-Roman

civilisations viewed contemporary tribes living further north as “barbarians.”

This has not deterred the descendants of the so-called barbarians from grafting

themselves on to these ancient civilisations, even as they embellish them.

Remarkably, even going by the prevailing

triune (literature, architecture, and art) depicting the “classical,” Kemet

surpasses all civilisations in antiquity combined.[9]

Accordingly, Marimba Ani’s counsel to African scholars worldwide to resist

becoming “professors of white power” is a justified caution. A surreal

synthesis is transpiring here. First, our consciousness is truncated. Without a

considered connection to ancient Kemet, African histories begin “concretely''

from our various ethnic origin legends. Secondly, our consciousness is

inverted. Alienated from Kemet our classical civilization, our minds are

rendered wide open to fraudulent insinuations. The spectre of otherwise

brilliant African minds spewing Eurocentric and other group propaganda is real:

Ancient Greece is the fountain of philosophy, mathematics, architecture,

literature and so forth, is fraudulently lodged in their minds. This is inimical

to our creative imagination as a people.

As alluded, Africans are also known to have

fabricated origins. Or non-existent lineages. According to Professor Ogot, myth

making on origins[10]

is a common practice to achieve a considered uniform worldview, as deigned by

the ruling ranks. In this regard, eminent Ghanaian novelist, Ayi Kwei Armah,

describes how some griots in West Africa’s medieval Islamising polities[11]

were compelled to fasten royal lineages to the Prophet Muhamad in Arabia. This

provides another reason why Classical Kemet, for the purposes of this

discussion, transcends other historical civilisations in Africa: It was

independent (indigenous) in its speculative endeavours, which resulted in its

distinctive (African) practices, for the longest time.

Classical Kemet is also not easily pliable to

ethnic jingoism. Its antiquity, and the fact that many African groups have oral

intimations or or practices pointing to “Misr,”

affords logical restraints on such counterproductive tendencies. Kenya’s Dr.

Kipkoech Arap Sambu’s thesis[12]

is an example of these contemporary African ties to Kemet. Through a study of

oral history, comparative linguistics, and religion, he provides a rich

background and a persuasive connection of the Kalenjin peoples to ancient

Kemet. Dr. Sambu parallels Cheik Anta Diop’s in this respect. The latter also

applied linguistic comparisons between Medu Netr (the language of the Kemetyu),

Wolof and other West African languages[13]

and confirmed significant relationships. Before we move to outline aspects of

Classical Kemet Civilisation that can be incorporated into the currently unfolding Basic Education Curriculum Framework (BECF)/ 2-6-3-3,[14] we feel compelled to cite Guyanese Professor of

Logic and Greek, George GM James.[15]

Undoubtedly, everyone who has

gone through the Kenyan education system has some notion of the ancient Greeks’

prowess in philosophy. Names such as Socrates, Plato, Aristotle stand out,

although their actual teachings may be less familiar. Pythagoras is of course

known by all geometry pupils, though many may be unaware that he was also a

philosopher. This powerful aura of a philosophising tradition further lends

credence to Greece being the epitome of “classical” civilization. Professor

James demolished this lofty image in his famous work, “Stolen Legacy.”

Aristotle’s incredibly prolific and varied genius as exposed by

Professor James is conspicuous. Here is a Greek philosopher, who wrote up to

1000 books in different fields! This outlandish intellectual fecundity was

achieved not in Greece, but curiously, in Kemet. Alexander “the great, ‘had appointed

Aristotle in charge of the library in Alexandria (a city the Kemetyu called

Raqote), in reality, a locus for the gathering and translation of the

intellectual works of the now conquered Kemetyu into Greek. Professor James is

categorical: the Greeks were at least 5000 years behind Kemet in scientific and

philosophical knowledge.

The psychological impact on the young African mind socialised to be in

undeserved awe of classical Greece (and hence its inheritors) is incalculable.

Such frauds must cease. At the very least, Kenyan youth must be furnished with

the truth in a considered manner.

Meanwhile, look who is studying

Kemet

The study of ancient Kemet (Egyptology) remains an invariably

non-African affair. Egyptology degrees are offered in only two countries in

Africa, namely in South Africa’s Stellenbosch and in six universities in the

Egyptian Arab Republic. The field is dominated by over 70 American, European,

Asian, including Australian and New Zealand universities and institutes[16] .

This reflects the huge importance of Kemet in human affairs to date. However,

Africans, the initial heirs of this stupendous legacy remain largely

indifferent to its practical application today.

Envision a conglomeration of African universities and institutes

positioned in Rome or Greece. Picture them dominating the research processes on

the antiquities of these European countries, including archaeological digs, publishing,

and teaching. Additionally, based on the ruins of ancient Rome and Greece,

imagine a motley assemblage of Africans creating all manner of cinema, novels,

documentaries, multimedia media productions including computer games, in their

image and fancy. And in doing so, generating a lucrative economy for

themselves, even as their actions alienate the Europeans from these two ancient

civilisations that are conceivably of European heritage. Now look at Classical

African Kemet. The curriculum can begin to cure this spectacular distortion of

the African imagination.

Classical Kemet and the BECF

What then, might we insert regarding Classical

Kemet into the BECF? Chimanda Ngozi Adichie, the celebrated Nigerian novelist

has revealed that Chinua Achebe “gave” her the “permission to write”[17]

for a global audience. She felt emboldened by an internationally acclaimed

novelist who looked like her. Classical Kemet provides our youth with the

“permission,” and we dare say, the imperative, to pursue the humanities and the

natural sciences as a natural course. The superlative and pioneering technical

achievements of Kemet, alongside its sublime, yet practical moral ideal and

spiritual system are an indigenous African heritage. Kenyan learners need no

longer suffer a distorted consciousness due to an indefensible gap in the

curriculum. We repeat, this is a matter of principle. The following are

distilled features of Classical Kemet, pertaining to the goals of the BECF. The

pedagogy (how to teach) is beyond the scope of this discussion.

The BECF vision is to “enable every Kenyan to

become engaged, empowered and ethical citizens,” through the provision of a

world class education. Its mission is to “nurture every learner’s potential”.

Through the provision of “pathways” to facilitate different talents, previous

disproportionate association of academic acuity to success is abandoned. The

vision and mission of the BECF are supported by four pillars, viz. National

Goals of Education, Principles, Values, and Theory.[18]

The four pillars inevitably overlap, differences

being in focus. Here, we concentrate on the dominant cross cutting issues of

concern, splitting them in two overarching clusters. We then link the clusters

to some pertinent facts on Classical Kemet that could be applied to bolster

curriculum content.

The two clusters generated from the four pillars of

the BECF are ethics-oriented; and excellence-oriented. The largely ethics-oriented

cluster of the curriculum comprise the following: Nationalism, patriotism

and unity; participation in the family, community, country and internationally;

moral and religious values; self-discipline and responsibility; intra-cultural

empathy; and care for the environment. The strongest aspiration in the BECF

regarding this cluster, is that the curriculum would produce learners who do

right for its own sake.

Religious Education (RE) through Christian

Religious Education (CRE) , Islamic Religious Education (IRE) and Hindu

Religious Education (HRE) are a key platform identified in the BECF to achieve

the above. However, RE has been part of the core curriculum of the 8-4-4 since inception

in 1985. In a 2012 study, by Itolondo[19]

, most secondary school student respondents declared their view of

CRE as relatively unimportant, despite enjoying it. Its utility came in

inflating their KCSE grades. This instrumental attitude means that the moral

teachings provided in RE, are not internalised as desired. There is no

indication from the BECF document that this will change. Bear in mind that RE

is a compulsory subject right through to junior secondary level in the BECF. A well-designed

infusion of content on Classical Kemet’s moral philosophy will augment the

curriculum goals in this regard.

Professor

Theophile Obenga explains that maat was the basis of Kemet’s moral

universe. The cosmic, social and individual levels of existence were steeped in

maat. Embodied by a female principle (“Goddess''), maat denoted

universal order, harmony, balance, reciprocity, justice, truth, and moral

rectitude[20] .

This elegant moral system was practiced, while literature on it existed millennia

before the West began to document moral treatises, Christian or pagan.

Obenga explains that the Kemetyu’s fidelity to the

principles of maat, from peasant to pharaoh, meant essentially that they

equated the law with morality. Professor Maulana Karenga expounds on the

“problem of evil” in the Kemetu’s mind.[21]

Maat signified balance and order, while “isfet” represented evil,

equated with chaos. From the creation of the cosmos to social interactions and

individual living, a constant struggle between isfet and maat permeates

reality. In other words, humans did not fall from grace due to some “original

sin.” Karenga expounds on the Kemetyu deep aspiration to be viewed as worthy by

fellow humans. Demonstrated moral rectitude, viz. responsibility to community

and authority, and empathy for the less fortunate, were highly valued. By

thinking, speaking, and doing maat, one transcends one's base instincts,

thereby defeating isfet. In doing so, one achieves “geru maa”

(firmly self-disciplined) status. This internal pursuit of moral and ethical

perfection reflected intelligence.[22]

“...If you wish your conduct to be perfect and free from all evil, guard

against the vice of greed…” wrote Ptah Hotep over 2300 BCE, quoted by Karenga.

“The Maxims of Ptah Hotep,” and numerous others like “The Instructions of

Kagemni,'' focusing on the virtues of self-control, have rich teachings

applicable today. This is regardless of religious persuasion or ethnicity. They

are African teachings par excellence.

In sum, previous formulas for imparting morality to

learners routinely resulted in superficial uptake. The infusion of relevant

content from Classical Kemet will reinforce the RE activities, resulting in learners

enhanced critical thinking on ethics and morality.

We return to the second overarching cluster

extracted from the BECF: the general aspiration that each learner achieves

excellence. Within this cluster are openings for the infusion of facts on

Classical Kemet. Such as within the constructivist theories informing the BECF.

These theories assert that learners build knowledge in unique ways based on their background and connection to stimuli around them. We interpret this to mean that if an African learner is largely clueless about her Classical past, then her vision of the world (and hence the knowledge she will construct from it), will be somehow warped. This is regardless of the learner’s natural talents. If an African child is going to learn the Pythagoras theorem, he must also know that Pythagoras spent twenty-two years in 6th century BC Kemet[23] learning astronomy and geometry. Omissions of such data, strewn across the curriculum, results in the child internalising distortions about Africans and other peoples. The astounding achievements of Africans at their best as independent thinkers (Kemet being the exemplar in antiquity), has bequeathed humanity with incalculable benefits.

Most subjects offered by the BECF can be linked to some achievement of Classical Kemet, thus filling the lacuna alluded to. As learners make their entry into the chosen senior school pathways (Arts & Sports Science; Social Sciences; or Science, Technology, Engineering & Mathematics/STEM)[24] they will have (known) many examples of African priority and excellence relevant to their interests and talents. It bears repeating that these few examples presented shortly, are of such gravity that any reasonable person should wonder why Kemet would be (largely) absent in the curriculum for an African learner.

First, let us be very clear: Kemet was not a magic-obsessed culture with “ignorant philosophy” according to portrayals by some scholars. Dr. Tdka Kilimanjaro explains that the Kemetyu did not separate science from myth or the material from spirit[25] in their worldview. Interesting how aforementioned scholars focus inordinately on the myth aspect of the Kemetyu, thereby distorting meanings. The evidence that such scholars are the ones fantasizing is right before our eyes, even today. Professor Obenga:

“...the entire range of ancient Egyptian civilization...canals, artificial lakes, statues, pyramids, obelisks, colossi, palaces, agricultural infrastructure, ...ceramics and its mummification skills, presents itself as the systematic application of science to production.[26] Their invention of writing and the alphabet favoured scientific development..."

Tdka Kilimanjaro states that the invention of writing by the Kemetyu was a “quantum leap” in human progress as temporal and spatial impediments to the spreading of knowledge were shattered[27] . They (Kemetyu) taught it to the Phoenicians, the source of the Greek alphabet, which, in turn, influenced an array of European alphabets, including the Roman one, in use here.[28] According to linguistic Professor Rkhty Amen, Medu Netr holds the most ancient and largest corpus of a written African language.[29] Additionally, ancient Kemet, produced more literature than all ancient civilisations. Egyptologist Miriam Lichtheim’s anthologies[30] reveal the practice of categorizing this literary profusion as monumental inscriptions (biographies), pseudepigrapha, royal inscriptions, royal decrees, theological treatises, didactic (moral) , songs and hymns, lamentations, prayers, prose tales, and love poems.

The physical evidence of sophisticated science suggested

above, means that the Kemetu applied mature mathematics. Theophile Obenga

demonstrates that ancient Kemetu invented mathematics[31]

. His adroit analysis of some of the problems in the so-called

Rhind, and Moscow Papyri are edifying. The Rhind Papyrus was authored by Ahmes

around 1650 BC, copied from an earlier work. It contains 87 problems. The

Moscow Papyrus was authored around 1850 BC and presents 25 problems.

At this moment in history, there is no Greco-Roman,

nor Islamic civilisation.

Chinese and the Hindu civilisation’s entry into

mathematics is yet to come from 1200 BC onwards. Kemetu, from Africa, had

conceived of mathematical problems beyond basic arithmetic. The Rhind Papyrus

presents first order algebraic equations. Another fragment (Berlin Papyrus,

dated 1900BC) contains a second order algebraic equation.

The Rhind Papyrus also has problems on arithmetical and geometrical progression, volumes of rectangular, cubic and cylindrical shapes, areas of triangles, circles, rectangles, trapezia. The ancient African Kemet’s value of pi was the closest to the contemporary value in all of antiquity. Trigonometric problems, calculations of the mass of a pyramid, the volume of a cone, differential factors, inverse proportions and the harmonic mean are also in the Rhind Papyrus.

The Moscow Papyrus presents a method of working out the volume of a truncated pyramid with a square base. Surely Kenyan learners should feel empowered and challenged to pursue STEM, not as proxy students of the ancient Greeks and others, but as the legitimate inheritors of a mathematical and scientific heritage. Empty myth and magic cannot erect colossal monuments.

The astounding Karnak temple complex in

Luxor exemplifies this. It is by far the largest in the world.[32]

Notice the columns and capitals topping them[33]

. The Parthenon in Athens, Greece; Capital Hill in Washington DC;

and the McMillan library in Nairobi manifest the influence of black African

architectural genius from millennia ago.

Dr Tdka Kilimanjoro provides an outline of ancient

Kemet’s achievements[34] :

The twelve-month calendar in use today, draped in the names of Roman deities

and emperors, is based on ancient Kemet’s. Kemet also had a “galactic” calendar

with one year equal to 1460 solar years. The galactic calendar was already in

use in 4236 BC. This year occurred when the distant star Sirius (Sopdet)

aligned with the sun and earth. This very ancient knowledge could only be

attained through meticulous observation and calculations of the movements of

heavenly bodies- the science of astronomy.

Meanwhile, to some people, everything before their

AD 1 or 1 CE (“Common Era”) is prehistory, demonstrating a radical audacity.

Agriculture was established in Kemet 17,000 years ago. Textile processing and clothes

making, with linen being the main material, were important activities. The dyes

and acids used reveals knowledge in chemistry. This pioneering scientific

knowledge was applied in ink development for artwork and writing, which were

available in different colours. Between 7000 to 5000 years ago, the Kemetyu

were progressing in metallurgy.

Kemet was a trailblazer in medical practice. They

had cures for various illnesses through interventions in internal medicine,

surgery, dental operations and pharmacy. Papyri texts demonstrate their superb

knowledge of human anatomy and physiology. Medical doctor Charles Finch,

expresses amazement at their ability to describe some particularly complicated

vertebral dislocations without X-ray technology.[35]

Today, Hippocrates, the ancient Greek doctor, is honoured by medical students

worldwide. Hippocrates was a student in Kemet. Ironically, Imhotep, the African

(Kemetyu) polymath, whom the Kemetyu regarded as the “inventor of healing”

preceded Hippocrates by 2000 years. Imhotep’s medical skills were so revered in

his lifetime and beyond, that even Greco-Romans deified him as Asclepius, Greek

god of medicine.[36]

The unification of Upper and Lower Kemet by Pharoah

Mena (Menes/Narmer) in 5660 BC inaugurated Kemet as the first federal nation in

history[37] .

He united 42 existing city-states called Sepet. Hundreds of Nile Valley

monarchs had preceded him.[38]

Is all this “prehistory”? Who determines that and what does it mean?

Ancient Kemetyu skills in painting, drawing,

sculpture and crafts, glass works, remain impressive. Kenyan learners have only

to be directly exposed to the exquisite works of those who came before them,

for inspiration and technique.

Conclusion

A sober look at Western and Eastern polities, reveals that their classical civilisations are guiding motifs suffusing their governments and societies. The “classical” is so decisive, that some powers have seen it fit to plagiarize aspects of Africa’s heritage for themselves. This “classical” aspect is really the seed of “culture and tradition”-the ultimate teacher. Our education curriculum, the obvious platform to instil the best of who we are, presents a gaping lacuna on this vital aspect. This squandering of a stupendous African heritage is inexplicable. Classical Kemet's moral and technical example is an indigenous African heritage that the BECF must inculcate as a principle. Unsurprisingly, Classical Kemet’s infusion in BECF dovetails with the latter’s stated objectives.

END

*The writer is the author of "The past IS PRESENT ahead of time", available in Amazon:https://www.amazon.com/past-PRESENT-ahead-time-novel-ebook/dp/B0BY1N2XYH/ref=sr_1_1?crid=2KKJMEUNFJXC2&keywords=mboya+ogutu&qid=1684887944&sprefix=mboya+ogutu%2Caps%2C393&sr=8-1

[1] Fela Kuti, “Teacher Don't Teach Me

Nonsense” 1986, Barclay

[2] “The Fitzwilliam Museum - Home | Collections | Ancient

World | Egypt | Kemet.” 2010. Www.Fitzmuseum.Cam.Ac.Uk. November 8, 2010. https://www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/dept/ant/egypt/kemet/virtualkemet/faq/index.html.

[3] Mundishi Jhutyms

Ka N Heru El-Salim, Spiritual Warriors are Healers (Montclair, NJ:Kera Jhuty

Heru Neb-Hu Publishing Company, 2003), 648.

[4] Ed. G. Mokhtar,

General History of Africa Abridged Ed. II Ancient Civilizations of Africa,

(California:UNESCO, 1990), 37,38, 40-42, 55

[5] Cheik Anta Diop,The African Origin

of Civilisation-Myth or Reality (Chicago:Lawrence Hill Books, 1974),xiv.

[6] Bethwel A. Ogot, My Footprints on

the Sands of Time ( Kisumu: Anyange Press Limited & Canada:Trafford

Publishers, 2003),392.

[7] “CLASSICAL | Meaning in

the Cambridge English Dictionary.” n.d.

Dictionary.Cambridge.Org.

Accessed October 10, 2020. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/classical.

[8] Marimba Ani, Yurugu, An

Afrkan-Centered Critique of European Cultural Thought And Behaviour (Baltimore:

Afrikan World Books, 2014), 551-2.

[9] KA2 Philosophy and Method, Ancient

Kmt (Egypt) Doctrine of Opposites, Modernized (University of Kmt Press,

2019),293, 312, 369-370.

[10] Bethwell A. Ogot, History of The

Southern Luo Vol.1 Migration and Settlement 1500-1900(Nairobi: East African

Publishing House, 1967), 17.

[11] Ayi Kwei Armah, Eloquence of The

Scribes-a memoir on the sources and resources of african literature

(Popenguine: Per Ankh, 2006), 173-4.

[12] Sambu, Kipkoeech. n.d. “Isis and

Asiis Eastern Africa’s Kalenjiin People and Their Pharaonic Origin Legend: A

Comparative Study.” Accessed October 10, 2020. http://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/10500/17655/1/thesis_sambu_ka.pdf.

[13] Cheik Anta Diop,The African Origin of Civilisation-Myth or Reality (Chicago:Lawrence Hill Books, 1974),184, 190-191.

[14] “Basic Education

Curriculum Framework 2017 KENYA INSTITUTE OF CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT.” n.d.

https://kicd.ac.ke/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/CURRICULUMFRAMEWORK.pdf.

[15] George G.M. James, Stolen Legacy-The

Egyptian Origin of Western Philosophy (Middletown, DE:Traffic Output

Publication, 2014), 9, 43, 89, 90, 94, 100-103, 117-118, 127-130.

[16]

“Universities That Offer Egyptology Degrees.” n.d.

Www.Guardians.Net. Accesssed October 10, 2020. http://www.guardians.net/egypt/education/egyptology_universities.htm.

[17] http://saharareporters.com/videos/video-achebe-gave-me-permission-write-says-chimamanda-ngozi-adichie

[18]

“Basic

Education Curriculum Framework 2017 KENYA INSTITUTE OF CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT.”

n.d. Accessed October 10, 2020. https://kicd.ac.ke/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/CURRICULUMFRAMEWORK.pdf. , 11-20

[19]Itolondo,

2012. The role and status of Christian Religious Education in the school

curriculum in Kenya

[20]

Theophile Obenga, African

Philosophy: The Pharaonic Period, 2780-330 (Popenguine, Senegal: Per Ankh,

2004), 189-192, 219.

[21] Maulana

Karenga, MAAT, The Moral Ideal in Ancient Egypt, A Study in Classical African

Ethics (New York: Routledge, 98, 2004, 203, 204,207.

[22]

Tdka Kilimanjaro, KA2 Philosophy and Method, Ancient Kmt (Egypt) Doctrine of Opposites, Modernize (University of Kmt

Press, 2019), 420.

[23] Theophile Obenga, African Philosophy: The Pharaonic Period, 2780-330 (Popenguine, Senegal: Per Ankh, 2004),156.

[24] “Basic Education Curriculum Framework 2017 KENYA INSTITUTE OF CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT.” n.d. https://kicd.ac.ke/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/CURRICULUMFRAMEWORK.pdf. ,54.

[25] Tdka

Kilimanjaro, KA2 Philosophy and Method, Ancient Kmt (Egypt) Doctrine of

Opposites, Modernize (University of Kmt Press, 2019), 464-465,478-480.

[26] Theophile

Obenga, African Philosophy: The Pharaonic Period, 2780-330 (Popenguine,

Senegal: Per Ankh, 2004), 429.

[27]

Tdka Kilimanjaro, KA2 Philosophy

and Method, Ancient Kmt (Egypt) Doctrine of Opposites, Modernized (University

of Kmt Press, 2019), 304,307.

[28]

Theophile Obenga, African

Philosophy, The Pharaonic Period, 2780-330 (Popenguine,

Senegal: Per Ankh 2004), 257-258

[29]

Rkhty Amen, The Writing System of

Medu Neter, Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs ( Institute of Kemetic Philology,

2010),vi.

[30] Distilled from

her “Ancient Eguptian Literature” Volumes 1-3

[31]

Theophile Obenga, African Philosophy, The Pharaonic Period: 2780-330 BC

(Popenguine, Senegal: Per Ankh, 2004), 430, 449-451.

[32]

Robin Walker, When We Ruled

(Baltimore: Black Classic Press, 2011), 195.

[33]

Mark,

Joshua J. 2016. “Ancient Egyptian Architecture.” Ancient History Encyclopedia.

Ancient History Encyclopedia. September 18, 2016. https://www.ancient.eu/Egyptian_Architecture/.

[34] Tdka Kilimanjaro, KA2 Philosophy and

Method, Ancient Kmt (Egypt) Doctrine of Opposites, Modernized (University of

Kmt Press, 2019), 307-311.

[35]

Robin Walker, When We Ruled

(Baltimore: Black Classic Press, Inc, 2011), 164.

[36] Mikić, Zelimir. 2008. “[Imhotep--Builder, Physician, God].”

Medicinski Pregled

61 (9–10):

533–538. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19203075/.

[37]

Robin Walker, When We Ruled (Baltimore: Black Classic Press, Inc, 2011), 162.

[38]

Tdka Kilimanjaro, KA2 Philosophy

and Method, Ancient Kmt (Egypt) Doctrine of Opposites, Modernized (University

of Kmt Press, 2019), 272.

Image of School Children source: freepik https://www.freepik.com/free-photo/group-african-kids-learning-together_13106446.htm#page=2&query=kenya%20children%20school&position=9&from_view=search&track=robertav1_2_sidr (accessed on 30/5/23)

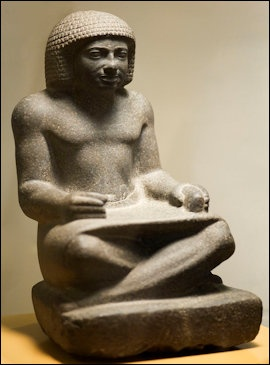

Image of Ancient Kemet scribe source:Facts and details: Ancient Egyptian Education. https://factsanddetails.com/world/cat56/sub404/item1929.html (accessed on 30/3/23)

Comments

Post a Comment